We are in the second month of 2018, and the United States has already seen its 18th school shooting. On February 14th, a domestic terrorist brutally murdered 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

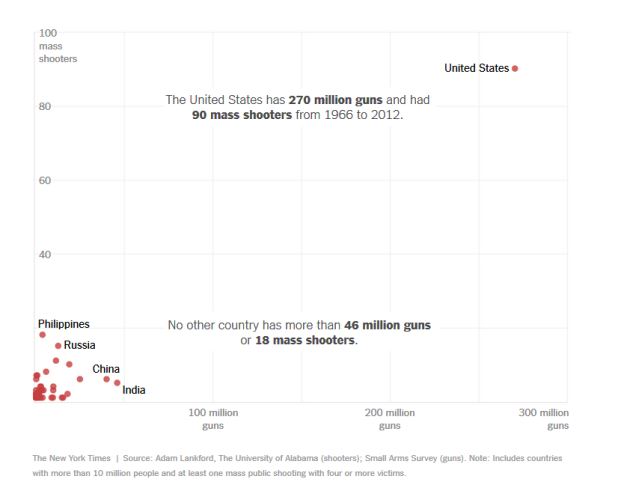

Rather than acknowledging that our country does, in fact, have a gun problem (see my blog post, “Gun Country,”) several politicians, including the president, have suggested that arming our nation’s teachers may prevent future atrocities from occurring. In response, many educators, including myself, posted selfies and messages under the hashtag #ArmMeWith.

Selfies and Messages from Educators Under the Hashtag #ArmMeWith

I spent quite some time scrolling through my fellow educators’ pleas. Some asked to be armed with school counselors and resources to help students experiencing mental health issues, others begged for “common sense” gun laws. Many noted that they could simply use more time for instruction and less time for standardized testing, but the request that I saw most often was for funding.

So let’s talk school funding. NPR’s Ed Team produced a highly informative series, “School Money,” which explores “how states pay for their public schools and why many are failing to meet the needs of their most vulnerable students” (Turner et al., 2016). If you are at all interested in learning more about how our nation funds our schools, I highly suggest checking it out, but I will explain the basics.

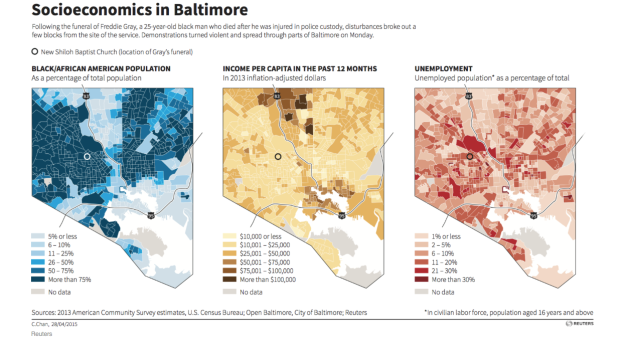

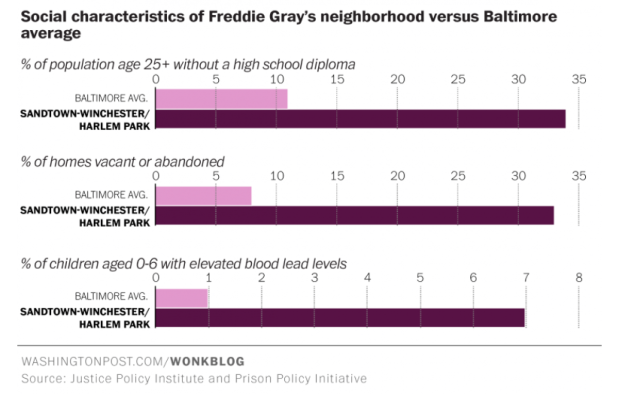

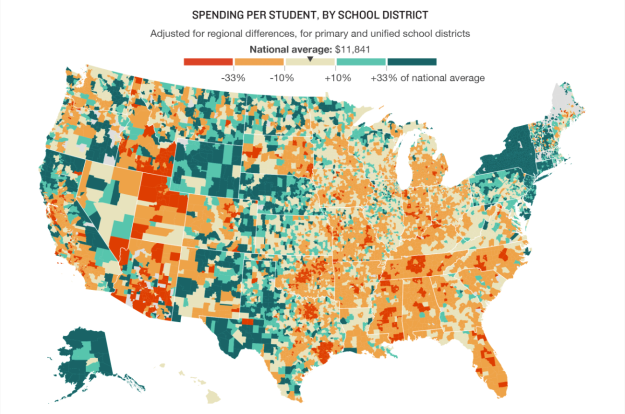

In the United States, our schools’ funding comes from a combination of three sources of money: local, state, and federal. While the percentage that each source provides varies from state to state, the average formula is something like this: 45 percent local money, 45 percent state, and 10 percent federal (Turner et al., 2016). The money that districts have to spend on each of their students ranges widely throughout the country. For example, growing up I attended two school districts in the same suburban county in New York. The district that I attended from first to ninth grade spends $21,303 per student each year. The district that I attended from tenth to twelfth grade spends $21,037 per student (Turner et al., 2016). The amount that these two districts spend on its students are roughly the same, and I’d argue that the quality of education that I received in each district was very similar. Baltimore City Public Schools, the district in Maryland in which I taught for three years, spends $15,528 per student. The opportunities that my schools in New York afforded to me were vastly different than those that my students in Baltimore received. However, it is important to note that the amount of funding spent on each student can vary drastically within a state as well.

With that said, why is it that some districts have more money to spend on their students than others? The answer is simple: property taxes. Property taxes differ significantly from neighborhood to neighborhood. In other words, the funding that a district receives is dependant upon the wealth of the residents in its zoned zipcodes. This automatically creates educational inequity as there is less money allocated to those districts located in the nation’s more impoverished neighborhoods. (Note: equality and equity are two different notions. Equality is giving everyone the same resources, opportunities, etc. Equity is giving everyone the resources, opportunities, etc. required to meet their individual needs). Some states, however, do contribute more to their schools’ funding in an attempt to alleviate some of this inequity. According to NPR, the national average that school districts spend per student is $11,841. Eighty districts spend more than $40,000 per student, while some districts spend less than $10,000 (Turner et al., 2016). An article published in NPR’s “School Money” series entitled “Why America’s Schools Have A Money Problem” includes an interactive map that can be used to research the amount of money that your district spends on each student.

In 2016, Baltimore City Public Schools faced a $130 million budget deficit. When the state of Maryland voted for the creation of several casinos, politicians told residents that the casinos would generate money for public schools. Baltimore’s Horseshoe Casino produced more than $200 million for the state’s Education Trust Fund in 2017 alone, yet Baltimore’s schools received less state money than they did the year prior. Instead, money put into the trust fund allowed the governor and lawmakers to reallocate other capital allotted initially for schools to things like roadwork and government employees’ salaries (Broadwater & Green, 2017). Despite resistance from the community, the state of Maryland is building a $35 million juvenile detention center in Baltimore. Many youth advocates have noted their concern that the state is investing money in jails while simultaneously providing less to schools (Anderson, 2017).

Student Protest Sign, Annapolis Budget Rally, February 2017

I am sure that those of us who grew up in higher socioeconomic communities can remember receiving a school supply list from our teachers every summer. Our parents would bring us to Staples or Office Depot and buy us infinite amounts of No. 2 pencils, our favorite brand of pens, scented markers, the Crayola crayon collection that had a built-in sharpener, folders and binders of every color, textbook covers, and loose leaf paper with hole reinforcements. When we reached middle school, our parents purchased us highly-priced Texas Instruments calculators. Our parents would also provide our teachers with boxes of tissues, rolls of paper towels, bottles of hand sanitizer, and packs of disinfecting wipes. Impoverished communities and inequitable funding, however, force teachers who work in less privileged districts to provide basic school supplies that are necessary for their students to learn.

When I first started teaching at a public charter school in Baltimore, I was given a completely empty classroom, along with four dry erase markers and an eraser. The school had two printers to be used by both middle and high school teachers. These printers were probably meant to be in a small office and therefore could not handle the constant demand for papers; needless to say, they were broken pretty much all of the time. My coworkers that had worked in other schools across the district told me that we were “lucky” because our school provided teachers with an unlimited amount of paper and did not ration the number of copies that we were allowed to make from each printer.

Not knowing whether or not the printer would be working when I needed to use it was too much stress for me. I bought a small printer for my classroom, but that is not nearly where my purchases stopped. Like so many teachers across our country that work in underfunded school districts, I purchased toner, paper, pens, pencils, markers, and other office supplies. I bought tissues, paper towels, hand sanitizer, disinfecting wipes. For my professional development, I bought books and software. Of course, I also bought decor to help make my classroom more welcoming and a place where my students wanted to learn, as well as candy and other snacks for when my students earned an extra treat.

My Classroom in the Public Charter School in Baltimore

I was fortunate to work at a school that purchased English teachers a class set of their required books. However, having multiple classes of the same course and only one collection of texts meant that the books had to stay in the classroom for students to complete their work. Any reading from the books that I wanted my students to do at home resulted in yet more photocopies.

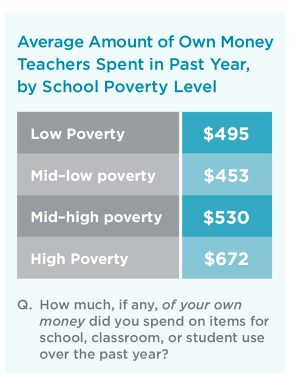

A survey completed by Scholastic found that teachers spend an average of $530 of their own money, and teachers that work in high-poverty districts spend nearly 40 percent more than that. During my two years working at the public charter school in Baltimore, I spent about $1,000 of my own money each year. When districts and families cannot afford to provide classrooms with resources, our nation’s teachers are forced to turn to crowdfunding websites to raise money to purchase supplies or fund projects. I must mention that America’s tax code does allow educators to take a deduction for the money spent on their classrooms. We can deduct a whole $250!! Please note that Republicans attempted to cut this number to zero in a preliminary version of the new tax code.

Inequitable school funding does not only affect a child’s access to school supplies. This winter we saw just one ramification of a district’s lack of funding when over 60 Baltimore City public schools closed due to freezing classroom temperatures, broken heaters, and pipes that burst. Funding determines school staffing, including the number of teachers, counselors, and custodians (just to name a few) found in a school. School funding dictates the courses that schools can offer; performing and fine arts are often the first programs to be cut when a district’s budget is tight. A student’s access to technology, extracurricular activities, and field trips are all affected by school funding, as well as teachers’ access to professional development. In this country, inequitable funding affects every facet of a child’s opportunity to receive a quality education. It is no coincidence that many of our country’s underfunded districts educate children of the global majority and children of impoverished families.

So when the president and other politicians that are in the pocket of the National Rifle Association try to tell the country that arming 20 percent of teachers would bring an end to school shootings, I have to roll my eyes. Let those actually in classrooms tell you what teachers and students need. Arm educators with funding and watch what we can do!